The News Not Noise Letter: Yes, Social Media Is Bad For Teens' Mental Health

The data you need to know and a perspective from someone who grew up on social media (and has the pics to prove it)

For regular updates, follow us on Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube.

Subscriber Zoom:

To those of you who are paying subscribers, please join me for a Zoom Wednesday, February 22 at 5pm PST/8pm EST. We’ll discuss social media and anxiety. RSVP: community@newsnotnoise.com. If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to join, you can make a one-time-payment here.

On Fridays I usually bring you News That Doesn’t Suck. But today I’m doing something a little different. This week lots of you have shared with me your concerns about mental health, anxiety and social media. Since I built this audience on Instagram and most of you found me through social media, I feel I have a special responsibility to address these issues and arm you with some data. In Monday’s newsletter, I shared details from an alarming CDC report documenting how teen girls in the US are experiencing record-high levels of sadness, violence, and trauma. On Wednesday, we took a look at social media and beauty pressure with supermodel, actress, and author Paulina Porizkova. Today, we’re tying together these two threads and looking at some disturbing data that shows teen mental health issues skyrocketed to a crisis only after Instagram hit the market in 2010.

The rest of this newsletter is written by Thalia Halloran, an NNN team member who is now in her 20s and was in middle school when these social media platforms arrived on the scene. She shares her personal observations and the hard data, much of which is from May 2022 Congressional testimony by NYU psychologist Jonathan Haidt.

Warning: this newsletter speaks frankly about mood disorders, self-harm, and suicide. These are highly sensitive subjects and they may bring up a lot of uncomfortable feelings. As always, we encourage you to take care of yourself however is best for you. If you are in need of immediate mental health assistance, you can reach the National Suicide and Crisis Hotline by calling or texting 988 or chat online here.

Teen Girls’ Mental Health Crisis:

Social media began taking off among teens in the 2010s. The very first iPhone was released in the summer of 2007. Facebook started allowing anyone age 13 and older to join in 2006, and Twitter launched in that same year.

Facebook and Twitter became places young users could write about their lives and opinions, but a whole new visual and video landscape hit the scene at the turn of the decade. Instagram launched in 2010, and Snapchat launched in 2011. And that’s when things started to change. Dramatically.

NYU social psychologist Jonathan Haidt put it best when he said that visual social media, especially Instagram, “takes the worst parts of middle school and glossy women’s magazines and intensifies them.”

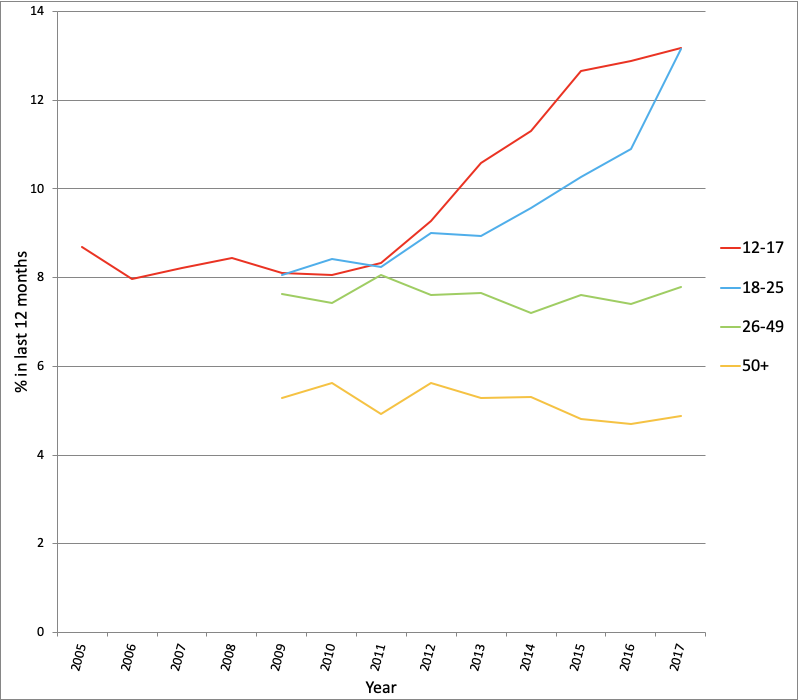

The following chart shows the percentage of people in different age groups who experienced a major depressive episode in the prior 12 months. You see that spiking red line? That reflects the rise in depression among 12-17 year-old Americans. The blue line shows depression rates for 18- to 25-year-olds.

Notice the sharp, steep, and ongoing spike starting around 2010? To understand how rare this is, Jonathan Haidt explains: “rates of teen depression and anxiety have gone up and down over time, but it is rare to find an ‘elbow’ in these data sets—a substantial and sustained change occurring within just two or three years.”

There is no similar spike for depression in older adults. And the skyrocketing depression rates are also highly gendered, impacting younger teenage girls far worse than everyone else. In 2017, one in every five teenage girls between the ages of 12 and 17 experienced a major depressive episode in the past 12 months.

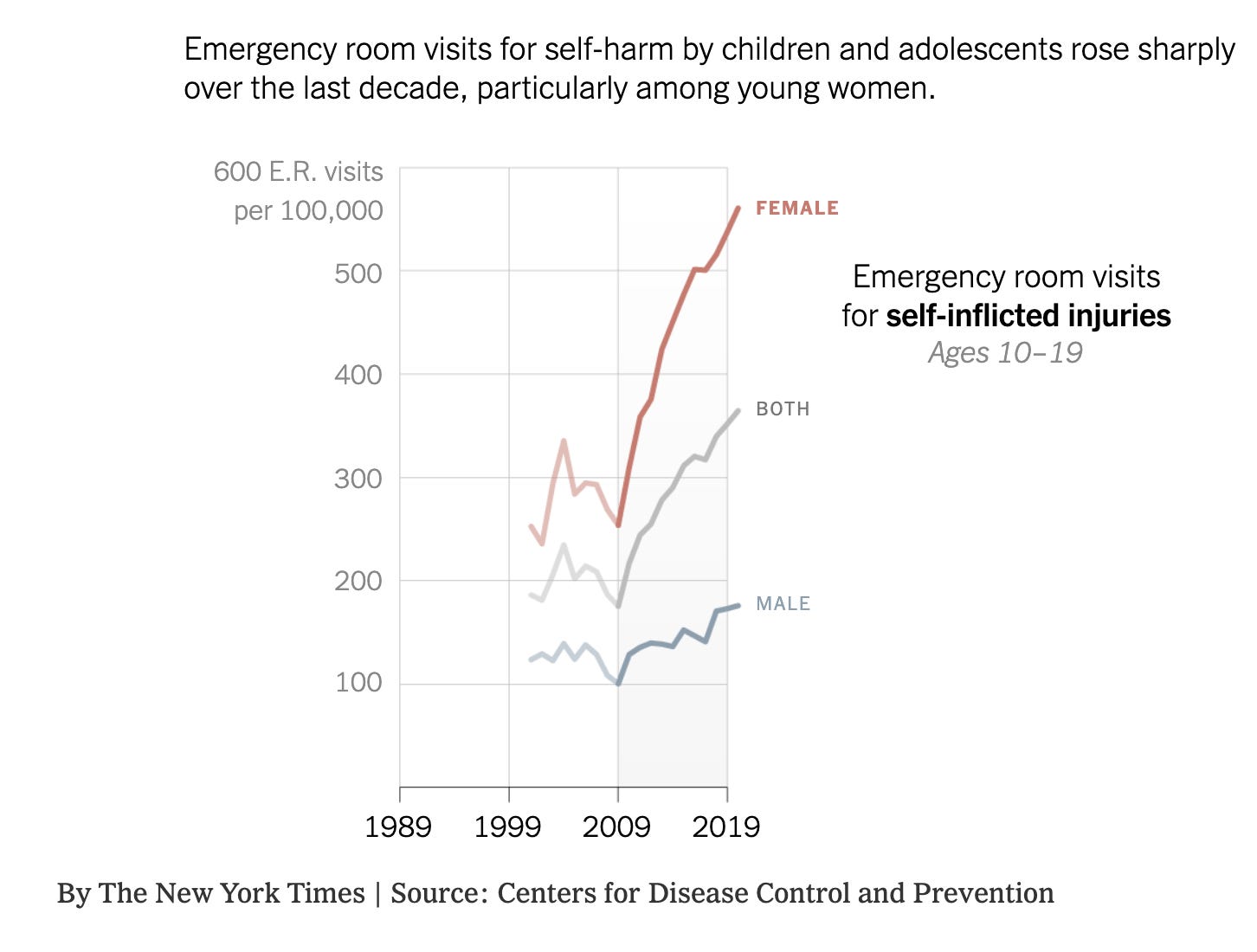

The next graph is truly chilling. It shows emergency room visits for children and adolescents for self-inflicted injuries before and after widespread use of social media. Check it out:

That nearly vertical line is almost unheard of. The rates have always been higher for girls than boys, but the data shows that while self-harm-related ER visits went up for both sexes starting in the early 2010s, the increase was far more dramatic for girls.

The kids are not alright.

I was in middle school when these apps were becoming popular, and remember vividly how influential they were. It wasn’t just the big names either. There were also a slate of smaller, more niche sites and apps that sprang up practically every week. Keek, ask.fm, Yik Yak, and numerous other bygone services were crucial to the social scene. I even remember friends lying about their ages to create Facebook accounts in the fourth and fifth grades. We had no understanding of these services’ data practices or safety, and neither did our parents. All we knew was that everyone else was using them, so we should too.

Posting on social media was exhilarating and terrifying at the same time. I would spend lots of time taking and retaking pictures to get them just right, tinkering with the captions to project the exact right brand. I think most of the time I was going for “casual, not trying too hard,” but in reality I was trying very hard. Once I hit “post,” I would check my notifications obsessively, refreshing to see if anyone had liked or commented. Instagram also used to have a feature where you could stalk the activity of people you were following, and I used this to see which of my peers were actively on Instagram at that very moment but hadn’t liked my post yet. I wondered why they hadn’t. I would analyze what I was doing wrong, what the cooler girls were doing differently, then I would puzzle out how to replicate their seemingly effortless flawlessness without looking like I was copying them.

My peers and I definitely suffered from social media usage. I had multiple friends who experienced eating disorders and a few who were involuntarily hospitalized for them. I also had friends who engaged in self-harm and/or who were hospitalized for suicide attempts. We were on “Sad Girl” Tumblr, stalked our crushes’ Instagram activity, obsessively analyzed our like and follow counts, used Snapchat filters to blur our acne and lighten our skin and reshape our facial features. Every in-person hangout and event turned into a photoshoot. We bought H&M clothes we’d seen on our favorite fashion influencers’ accounts, tried to perfect our angles to send Snapchats that were sexy-but-not-trying-too-hard, tormented ourselves about whether or not we had a thigh gap, texted one another mean comments about someone else’s cringeworthy posts, insisted on screening our friends’ group pictures to make sure our own faces looked good since we’d be tagged in the images. We workshopped photo captions in our group chats and harassed our friends to like our posts immediately after we posted them, because if someone else saw your post had zero likes, it would be ruinous. I distinctly recall deleting an Instagram post once because in the fifteen minutes since I’d posted it, nobody had liked it.

On a lighter note, I found this absolute relic, my first-ever Instagram post from when I just turned 13. This was back in the days when you could get away with an incredibly grainy photo and an overexposed filter. My IG handle is now my first and last name, but at the time it was @thaliawesome. Simpler times. I spent ages agonizing over what to caption it… I think I nailed it.

Social media was (and remains) fun and exciting, but it also meant that for the first time ever, pre-teens and teens had access to all the hurtful things our peers were saying about us around the clock and in our pocket. In middle school, one of my classmates was targeted by an anonymous account that commented “kys” – meaning “kill yourself.” It showed up on all her Instagram posts one day. In a would-be-heartwarming-if-it-weren't-so-heartbreaking show of solidarity, all the girls from school added nice comments under her posts and reported the “kys” from the mean account.

On social, young people aren’t just exposed to negativity from people they know. There are entire “pro-eating disorder communities” pervading social media, and according to the Duke Center for Eating Disorders, the average age of users subscribing to this sort of content is 17. Plastic surgeons have reported patients coming in with “Snapchat dysmorphia” who want to alter their faces and bodies to resemble their selfies through Snapchat filters. And studies have shown that teen girls in particular feel worse about themselves and their bodies after using photo-based social media like Instagram. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2021 that Facebook’s own data showed that Instagram (which Facebook owns) is detrimental to the health of teenage girls more than other apps.

Numerous studies have shown that digital media use, internet use, and social media use in particular have what is called a “Goldilocks effect.” As you might guess from the name, a Goldilocks effect means that there’s a “sweet spot” for usage, but if you go much past that point, the detrimental effects compound rapidly. Basically, a little social media can be neutral or even beneficial, but a lot of social media use is harmful to mental wellbeing.

These days I’ve drastically cut back on my social media usage. I curate who I follow and who I allow to follow me. I do my best to get around the algorithm and seek out posts that bring me joy instead of making me feel bad about myself. I’m an adult, and I have the emotional maturity to do that now. I didn’t have that ten years ago, but I did have access to social media.

Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said recently that he believes age 13 is too young for children to be using social media. He said that allowing children to access social media “does a disservice” to them. And plaintiffs have filed dozens of lawsuits against social media companies alleging that social media outlets are addictive products just like opioids and tobacco. The plaintiffs seek to hold these companies accountable for personal injuries which they say are a direct result of social media use. A consolidated version of these cases is in pre-trial litigation, and defendants include Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, YouTube, and their parent companies. Meta (Facebook and Instagram’s parent company) has instituted controls it says are designed to improve the platform’s safety for kids, and they dispute the plaintiffs’ filings in these cases.

We can’t lay the blame for the teen mental health crisis solely on social media. There are a lot of potential culprits, but we found Haidt’s testimony persuasive.

– Thalia Halloran

What do you think?

Do you allow your children to use social media? If so, at what age? How are you talking with them about social media and mental health? Let us know in the comments or by emailing community@newsnotnoise.com.

Special thanks to Dr. Samantha Boardman, MD who first brought Jonathan Haidt’s testimony to our attention. If you want science-backed advice on improving your mental health and wellbeing, check out her newsletter on Substack, The Dose.

Want more information?

Check out the latest episode of the News Not Noise Podcast, where we talk about vulnerability, beauty, and social media with Paulina Porizkova.

Paid subscribers to News Not Noise get an extra treat this week: a few more of Thalia’s early Instagram adventures.